Thanksgiving, explained

Thanksgiving may be synonymous with turkey and pie today, but its roots trace back to a 1621 feast between Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, who gathered to celebrate the settlers’ first successful harvest.

The “first Thanksgiving” most often refers to a 1621 meal between the Pilgrims and the Native Wampanoag people, though historians have uncovered earlier examples, including Spanish colonists who celebrated alongside the Seloy tribe in Florida in 1565 and Virginia settlers who took part in "a day of thanksgiving to Almighty god" in 1619.

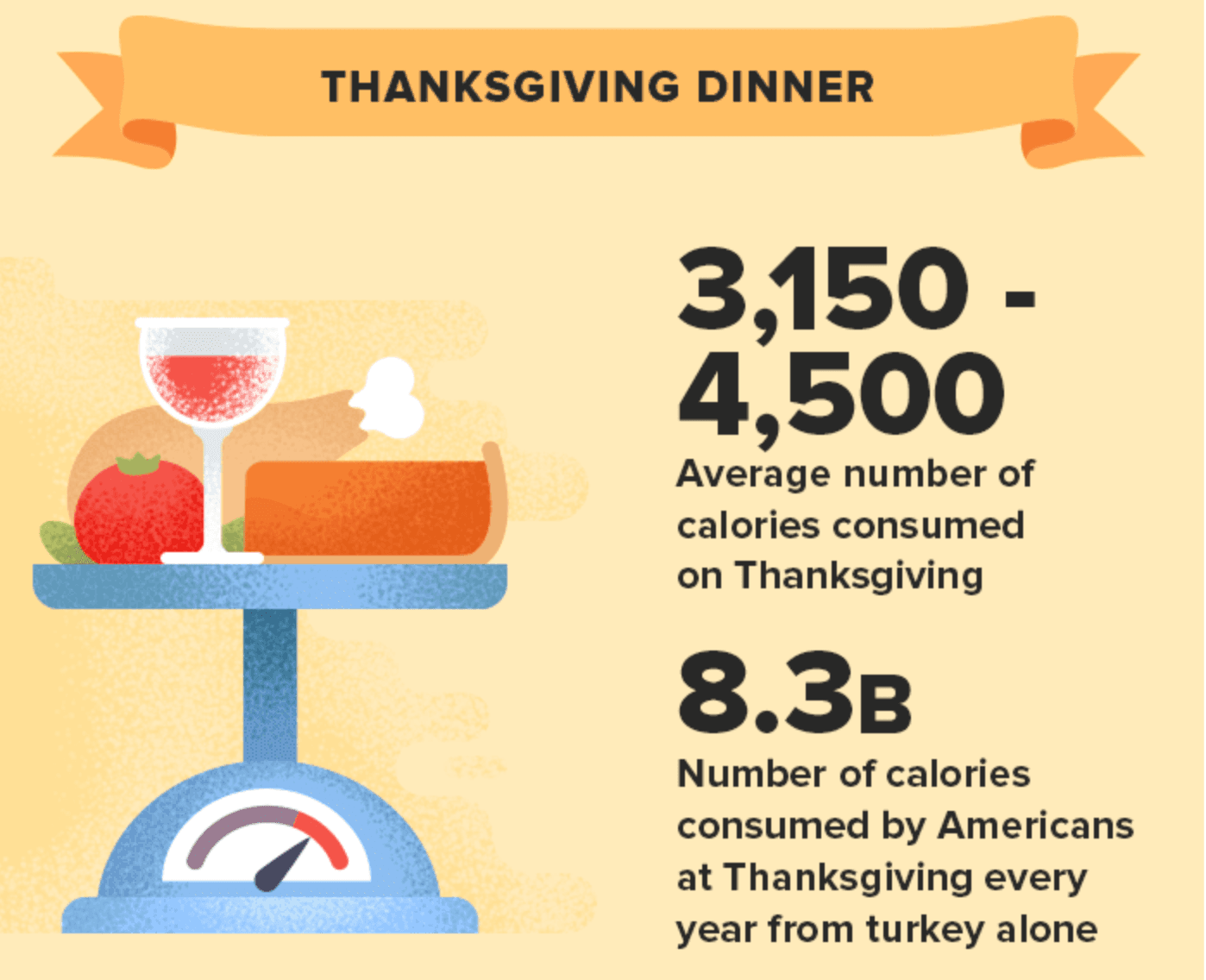

In 1863, Abraham Lincoln declared a national Thanksgiving Day to be celebrated on the final Thursday of November each year. (In the 1930s, it was changed to the fourth Thursday.) A large meal shared with loved ones is the centerpiece of most Thanksgiving celebrations, where the average gathering size is seven, and most people consume 3,150-4,500 calories.

What began as a neighborly meal to celebrate a successful harvest has transformed into an annual economic and cultural powerhouse: The day before Thanksgiving is one of the busiest days of the year for air travel as Americans prepare to eat upward of 40 million turkeys and 80 million pounds of cranberries.

Hours of research by our editors, distilled into minutes of clarity.

Thanksgiving may be synonymous with turkey and pie today, but its roots trace back to a 1621 feast between Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, who gathered to celebrate the settlers’ first successful harvest.

That's 50% of all whole turkeys sold in the US in a given year. (Most of the remaining 50% are purchased for Christmas.)

Individuals consume an average of 3,150 to 4,500 calories at the meal, which takes the average male 10 hours to burn off.

There is no record of turkey on that first table, though one account vaguely refers to "fowl." The meal mostly consisted of seafood and venison.

Agricultural knowledge was vital to the Pilgrims’ survival in a new, unknown land. Explore how to make sobaheg, a Wampanoag venison stew that would likely have been served at the first meal between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims.

Long before the 1621 meal between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés and 800 Spanish settlers founded the city of St. Augustine in Spanish la Florida. They celebrated the founding with a Mass of Thanksgiving with the Indigenous Seloy tribe.

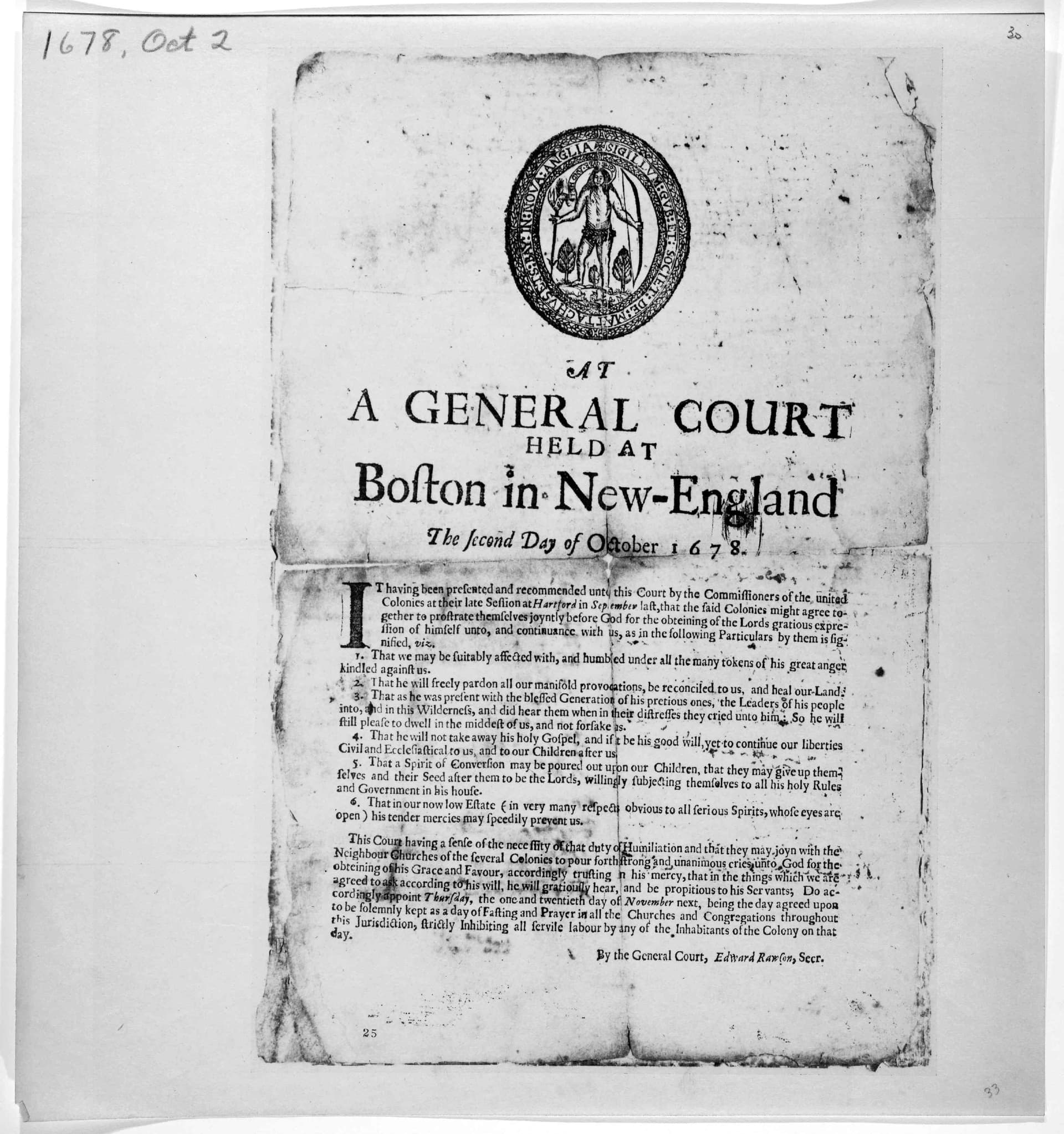

Although the Pilgrims' meal with the Wampanoag is often cited as "the first Thanksgiving," historians note a meal intended to mark "a day of thanksgiving to Almighty god" was celebrated by early settlers three years earlier. President John F. Kennedy acknowledged the day in his 1963 Thanksgiving proclamation.

A writer and abolitionist from New Hampshire, Sarah Josepha Hale was instrumental in cementing many of the Thanksgiving traditions we celebrate today. Her 1852 novel "Northwood, a Tale of New England," described a feast with a roasted turkey, stuffing, plum pudding, and pumpkin pie. She wrote dozens of editorials and letters to politicians campaigning for the day to become a national holiday. In 1863 she was finally successful in convincing President Lincoln to make it official.

History buffs will love this trove of original documents related to the Pilgrims and Thanksgiving, including 18th-century recipes, one of Sarah Josepha Hale’s appeals to President Lincoln to establish the national holiday, and a copy of Abraham Lincoln’s original 1863 Thanksgiving Day Proclamation. You can also find illustrations and photos of historical Thanksgiving celebrations over the years.

In the waning years of the Great Depression, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt attempted to move Thanksgiving up by a week, giving merchants a longer holiday shopping season. After pushback from lawmakers, he reversed course in 1941, permanently fixing the date of Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday of November.

Art, music, sports, entertainment, movies, and many other subjects—these elements define who we are as a society and how we express ourselves as a culture. Take a deep dive into the topics shaping our shared norms, values, institutions, and more.