We're breathing microplastics

White blood cells can’t fight off microplastics and that sparks inflammation and bigger health risks. They’re in our food, water, even the rain. What does that mean for us?

Microplastics, or MPs, are tiny plastic particles less than five millimeters long and have become one of Earth's most widespread pollutants.

Like synthetic plastics, MPs are mostly made of long chains of hydrogen and carbon atoms, formed by linking byproducts of refining crude oil and natural gas. Other chemical additives may be incorporated to modify the final product’s properties.

Primary MPs, such as microbeads, are intentionally manufactured to be small. Secondary MPs, such as those released while washing synthetic textiles, form from the breakdown of larger plastics and make up the bulk of MPs in the environment.

As of 2024, the FDA claims there is insufficient evidence that MPs pose any human health risk, though initial biochemical studies have linked them to inflammation and hormone disruption.

Hours of research by our editors, distilled into minutes of clarity.

White blood cells can’t fight off microplastics and that sparks inflammation and bigger health risks. They’re in our food, water, even the rain. What does that mean for us?

These tiny plastic particles come from intentionally small items and the breakdown of larger plastic debris, ending up in soil, air, and water. A study of 37 US National Park beaches found microfibers at every site, making up 97% of all microplastic debris.

Polyethylene and other plastics are formed by combining ethylene and propylene, which are produced through refining crude oil. These plastics are formed into pellets called nurdles, which are melted and molded to manufacture countless products.

Also known as nurdles, these tiny plastic pellets are extremely difficult to remove once spilled. Their chemical composition, which enhances absorption, causes them to contain higher concentrations of certain toxins than the surrounding environment.

Despite coming from petroleum, which itself comes from organic material, synthetic plastic was not mass-produced until the mid-20th century. Insufficient time has passed for microbes to develop the necessary enzymes to break it down naturally.

Synthetic fabrics shed millions of plastic microfibers during washing, which pass through wastewater treatment and end up in oceans, soil, and food chains. A single wash load can release several million microfibers, but washing with cold water can reduce this.

Ideonella sakaiensis, a bacterium found in recycling plant sludge in 2016, was the first organism seen to possess enzymes that could break down PET, a type of plastic. Researchers continue to search and try to bioengineer microbes that can digest other plastic types.

A 25-year study in Scotland found that sewage sludge used as fertilizer introduces various microplastics into soil, where they remain and degrade into smaller particles that worsen soil quality. Dyes found in microplastics may also be leaching into the environment, causing additional toxic effects.

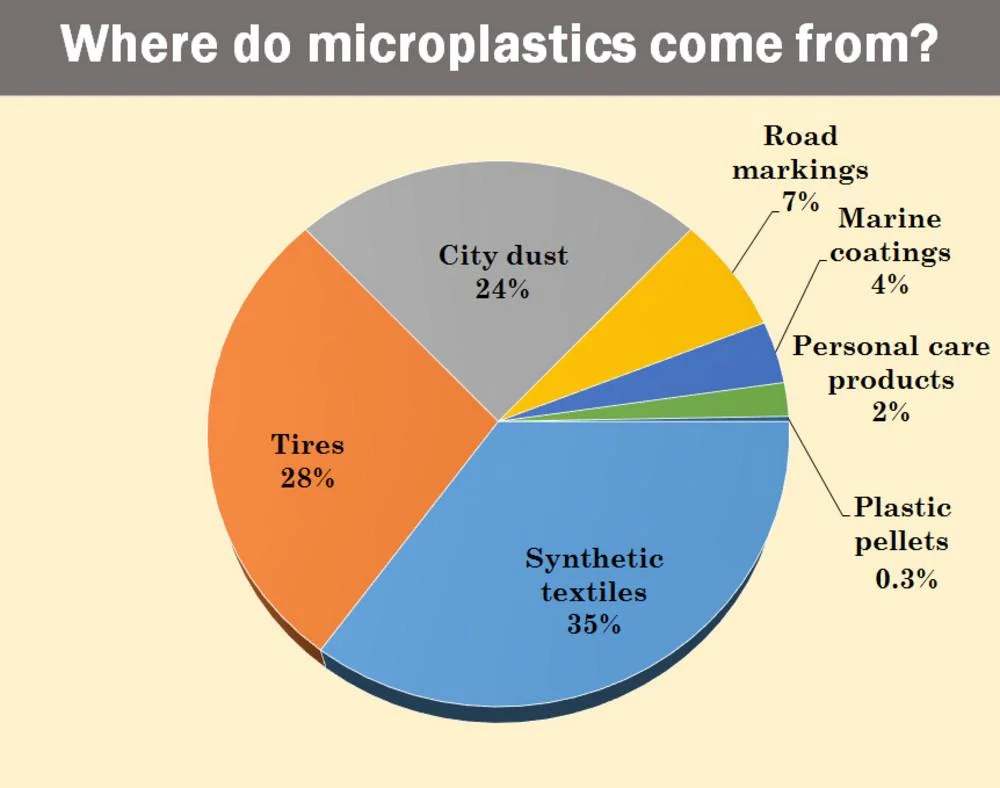

These sources contribute more than 60% of the primary microplastics polluting the oceans, followed by city dust and road markings. City dust is made of pieces of building coatings, synthetic footwear, and other human-made objects that have broken off due to weathering and abrasion.

Researchers have found microplastic particles in snow samples taken from near the summit of Mount Everest. Microplastics have also been detected in the Mariana Trench, highlighting the widespread nature of this pollutant.

Since our ancient human relatives began using stone tools to perform tasks, humans have harnessed scientific knowledge and new technologies to expand the boundaries of our understanding of the natural world. From quantum computing and microplastics to artificial intelligence and memory, explore these topics and more with our concise yet informative overviews and expert-curated resources.